Return to Emily Friedman home page

Originally published on June 2, 2015

Medicare and Medicaid became law 50 years ago next month. No statute has had more of an impact on American health care. And we are still fighting over it.

The letter was read by a physician to members of the Subcommittee on Problems of the Aged and Aging of the U.S. House of Representatives during a hearing in 1960 on a proposed bill to provide federal subsidies for medical care to certain populations, notably older people.

It read:

I am sorry that it had to end this way, but I see no other way … . If you will look over the drug bills, you can see that what little money we have could not last long … . Last month our drug bill was $83.31. The Thorazine shots for Mary are $1 cash each — sometimes two a day, besides the other medicine. Pray for us that God in his great mercy will forgive us for our act. (From A Sacred Trust, by Richard Harris, New American Library, 1966.)

The writer of the letter and his wife then committed suicide.

Those hearings were only one event in a 50-year struggle to make health care available to people who could not afford it. It was a long and bitter fight that can be said to have begun with Theodore Roosevelt's proposal for universal coverage for working people during his 1912 presidential campaign and progressed with the recommendation from the Committee on the Cost of Medical Care in 1932 that health care be available to everyone through prepayment (in other words, health insurance) and that medical care be provided by organized medical groups.

The American Medical Association went ballistic over the latter idea, with the enormously influential editor of the association's journal, Morris Fishbein, M.D., decrying group practices as "medical soviets." His views, which echoed those of his colleagues in the AMA leadership, would hold sway for decades. At the time, the AMA was the most powerful lobby in Washington, and it would be for another 30 years.

The American Hospital Association took an entirely different tack, embracing the idea of voluntary health insurance in 1933 and playing a central role in the creation of Blue Cross plans, which had an extremely close relationship with hospitals for many years (needless to say, both sides have since gotten over that).

Many bills were submitted in Congress over the years; most failed. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt originally had considered including broad federally subsidized health care coverage in the Social Security Act of 1935, but was forced to delete it after opponents threatened to torpedo the entire program.

In 1945, President Harry S. Truman floated a proposal for broad federal subsidy of care for people who could not afford it; this led to what became known as the Wagner-Murray-Dingell bill. Between AMA opposition and attacks by Truman's political enemies, it went nowhere.

However, in time, some progress was made, as in the passage of the Hill-Burton legislation in 1946, which provided federal funds for the construction or replacement of hospitals (largely rural, but others received grants), as long as they promised to provide care to the uninsured poor.

In 1960, the coming sea change was signaled by Congressional passage of the Kerr-Mills bill, which provided subsidies to states to pay for care of some low-income patients. This was largely the creature of Wilbur Mills (D-Ark.), the enormously politically skilled chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee, who had long supported subsidy of care for the vulnerable.

In 1962, President John F. Kennedy announced his support for subsidized care for all people older than 65 and, although the AMA expressed strong opposition and Kennedy was assassinated the next year, the writing was on the wall. The new president, Lyndon Baines Johnson, was one of the most adept manipulators of legislation — and legislators — in the history of the United States, and he wanted health care coverage for seniors and those who could not pay. The question was what the program would look like once it went through the meat grinder of Congress.

A camel, as the old joke goes, is a horse that was put together by a committee. No one should have been surprised that what eventually became Public Law 89-97, which was passed by Congress in late July 1965 and signed by President Johnson on July 30 in Independence, Mo., in the presence of former president Truman, was something of a mishmash. (Truman received the first Medicare card ever issued.)

From left, in the foreground: Wilbur Mills, President Lyndon B. Johnson signing Public Law 89-97, Lady Bird Johnson, Harry S. Truman, vice president Hubert Humphrey (just left of and behind Mrs. Truman) and Bess Truman. (public domain photo). |

Medicare, as it was eventually cobbled together, was a complex combination of political compromise, concessions to the private sector and public initiatives. In previous writings, I have described it as a three-layer cake (the third layer was Medicaid, and we will get to that). First, there was hospital coverage, paid for by taxes on employers and employees. Second, there was Medicare Part B that covered the costs of physician care, which would be paid for by premiums, as in private insurance. Nongovernment intermediaries (that is, private insurers) would determine what constituted "reasonable charges" and address other testy issues.

The law was designed in this way, in part, to assuage the enraged AMA, which, although it had lost the fight, was threatening a physicians' strike. Having private insurers play a pivotal role would, it was hoped, appease the powerful organization.

The strike did not come about, in part because Johnson invited AMA leaders to the White House after the law passed and made it clear that the federal government would not interfere with the practice of medicine or clinical decision-making and that he did not want any more trouble from organized medicine. He didn't get any, even though some of his promises have gone by the board over the years.

Medicaid has had a much more volatile political history, in keeping with the controversy of its birth. The story is extremely complex, but the short version is that state governments, which had expected that they would play a role in Medicare, were, to put it mildly, irritated that it was going to be a completely federal program. They had to be placated.

The answer was Medicaid, the stepchild, the afterthought, which was a rider on the bill until very shortly before it was passed. Mills had wanted a program to subsidize care for low-income people, and he saw this as an expansion of the existing Kerr-Mills grants. Medicaid would be a state-federal "partnership" (and we all know how well that arrangement has fared), with the feds providing matching funds on a sliding scale depending on the wealth of the state in question, and the states having wide flexibility in terms of eligibility income level, benefits beyond the basic federally mandated package (which was so vague as to be open to massively different interpretations) and administrative approaches to running the thing.

Furthermore, a provision in the law allowed the states to apply for waivers so they could experiment with the program, thus making Medicaid beneficiaries the lab rats of the U.S. health care system to this day. The first major experiment was in Arizona, which flatly refused to participate in the program unless Medicaid beneficiaries could be enrolled in private health plans. The feds eventually agreed, and Medicaid managed care was born in the form of the Arizona Health Care Cost Containment System. States have been fooling around with Medicaid ever since, often with good results and sometimes not so much.

One reason that Medicaid has such a checkered past is that it was grafted onto what was then known as the "welfare" system (now known as Temporary Assistance for Needy Families) — that is, the state agencies that would run the programs were, for the most part, the entities that administered payments to certain extremely low-income groups, including women and children, pregnant women and some disabled people. And although these agencies were ill-equipped to do so, they also inherited responsibility — in the all-time sleeper in the history of U.S. health policy — for people in need of long-term care. The provision in the law that made funding available for such care was noticed by almost no one and, in the 50 years since, it has become both a lifeline and a nightmare.

Medicaid was stigmatized from Day 1. Because of its association with "welfare" grants, and because its beneficiaries were, for the most part, low-income, it was, as one observer said at the time, "a poor program for poor people." Indeed, even in statute, those benefiting from it were known as "recipients," a significantly less dignified term than "beneficiary," as those who qualified for Medicare were denoted.

The stigma continues to this day. There is a reason that the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services is universally referred to (by design, in my opinion) as CMS, not CMMS. Medicaid is not the most popular kid on the block.

Many people complain (with good reason) about the unfathomable complexities of the Affordable Care Act, but we should remember, in these latter days, that although the law has many stupid provisions, its creators at least had the benefit of some decent data (not as many as they should have, but we'll discuss that another time) and analysis from the health services research community. In 1965, the authors of P.L. 89-97 were flying by the seats of their pants.

For one thing, the AMA kept insisting that more than 90 percent of Americans already had health coverage, so Medicare was not needed (although the AMA did support passage of Medicaid, a fact that has been lost to history). Wilbur Cohen, a federal official who wrote much of the Medicare and Medicaid law and who later served as secretary of what was then the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, told me in a long-ago interview that no one thought there were that many uninsured people and that the law would cover only "a few residual cases." Wrong. As he admitted, it turned out that there was "a huge subterranean population."

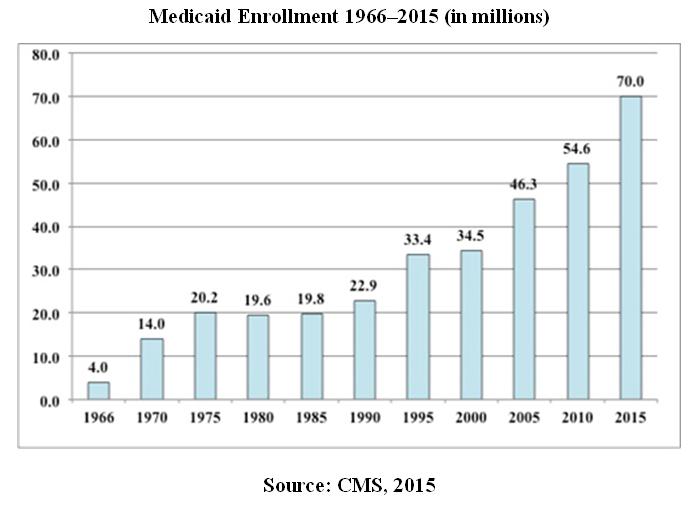

Because Medicare was, for the most part, limited to people 65 and older, it was somewhat easy to predict what its enrollment would be. But Medicaid was a surprise. The "subterranean population" would only grow, until Medicaid became the largest single health care coverage program in the United States.

|

Estimates of costs also were way off, although advocates of the law may have been playing a bit of lowball. In any case, the estimate for annual Medicaid costs in the first year or two was $238 million; actual expenditures were $2.27 billion in 1968, and the program was not fully implemented at that time.

One reason for this is that some states, which already had been spending huge amounts of their own funds on care for low-income uninsured people, knew a gravy train when they saw it. The poster child was New York, which, once the law was passed, promptly made 45 percent of its population eligible for Medicaid.

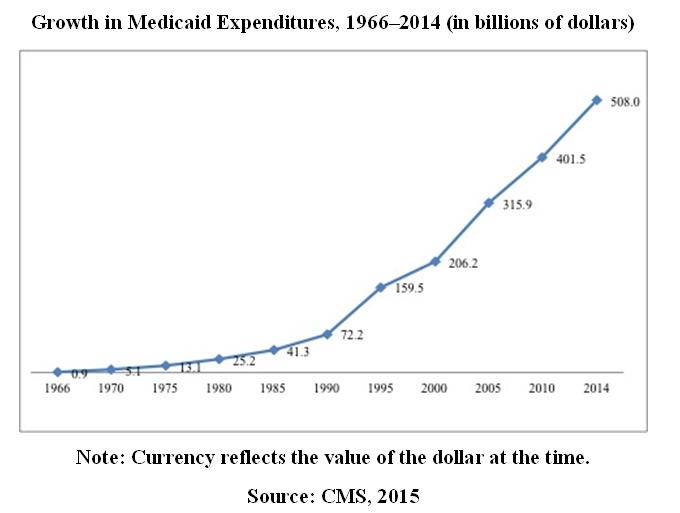

That action, in turn, led to the first efforts by Congress to control Medicaid costs, and the battle between the feds and the states escalated. It still goes on. And Medicaid spending has skyrocketed for 50 years.

|

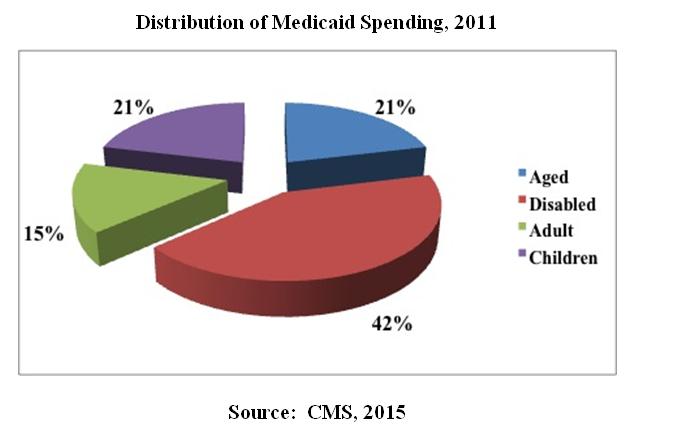

However, although it is the low-income population — largely women and children — who have borne the brunt of Medicaid's political slings and arrows, they are not the main drivers of Medicaid spending. For reasons that are obvious to any health care professional, the disabled and the nursing home population consume the bulk of Medicaid dollars. They need a lot more care than healthy mothers and children.

|

Medicaid also has become something of a Christmas tree of benefits; its scope has expanded significantly over the years. There was pressure from the federal government to raise the income ceiling for pregnant women to 185 percent of the federal poverty level, and many states complied. Income-eligibility ceilings were raised in some states for other groups (and, unfortunately, lowered in others). After a bitter battle, persons with HIV or AIDS were included among the disabled who could qualify for Medicaid coverage. Screening for and treatment of illness in children eventually was covered, and in some states, the Children's Health Insurance Program (CHIP) was added to the Medicaid benefit array.

And, of course, the latest attempt was the ACA provision allowing states to increase the income-eligibility level for all low-income persons to 138 percent of the federal poverty level, thereby ending decades of restricting the program to certain groups and, in some states, keeping the income-eligibility level appallingly low. Unfortunately for the architects of the ACA, it apparently never occurred to them that the governors and legislatures of certain states had no intention of expanding their Medicaid programs, even though the feds were going to pay the full cost of the expansion for the first few years, and even though some research (biased, but not radically so) has shown that Medicaid expansion actually saves states money.

Meanwhile, the sleeper provision in the law — coverage of people in need of long-term care — has continued to be Medicaid's nightmare. As Bruce Vladeck, Ph.D., former administrator of CMS (then known as the Health Care Financing Administration) famously said years ago, "Medicaid is the most egalitarian of all health coverage programs because, if you live long enough, you will end up qualifying for it."

Today, 9 to 10 million low-income frail Americans, almost all of them in long-term care, qualify for both Medicare and Medicaid, and the fight over who is going to pay the freight for their care is the latest in the endless battle between the states and the feds over this program.

There have been nursing home scandals in terms of both quality and outright fraud, yet there also have been huge jumps forward in terms of home- and community-based care, which costs less and is the preference of most older Americans.

It has all come at a cost — a very big cost. In 2014, Medicaid spent $123 billion on long-term care. That population, and other elderly beneficiaries, account for 63 percent of all of the program's expenditures.

Diane Rowland, executive director of the Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, said long ago that "[Medicaid] was the one train pulling out of the station to which you could attach improvements." And it has become a train with a lot of cars trailing behind it.

When he was commissioner of human services in New Jersey in the 1990s, William Waldman, now a professor at the Rutgers University School of Social Work, described Medicaid as "the Pac-Man of state budgets." (For younger readers, allow me to explain that Pac-Man was an early video game in which a yellow round critter ate everything in sight.) The quote has been ascribed to many political leaders since, but I first heard it from the New Jersey contingent.

Medicaid did become, in many states, the first or second most expensive public program. Given its constituency and its stigma, it would not take a rocket scientist to predict that its low-income beneficiaries (the elderly and disabled were usually exempt, due to federal law and effective lobbying by interest groups) would bear the brunt of budget cutbacks.

And they did; benefits were cut, often foolishly (not paying for dental care for low-income adults does seem rather shortsighted), and income-eligibility levels were lowered in lean times, and people thus rotated on and off the program, causing administrative nightmares and a great deal of wasted time and resources.

Health care providers paid the price as well. In the world of Medicaid, when in doubt, cut provider payments. After all, it was reasoned, they can cost-shift, and nonprofit hospitals are required to care for at least some of the poor, and emergency departments must evaluate patients and treat some of them, and so forth and so on.

If a policymaker wants to do something, he or she can always find a justification for it.

In some states, Medicaid is a decent payer. In others, it's a disaster. We all know that hospitals, physicians and all other providers believe they should be paid more than they get, but in many instances, Medicaid really does not even cover costs. And in the new health care landscape, cost-shifting ain't what it used to be.

Furthermore, many Medicaid beneficiaries are difficult. Sometimes it is their fault, and often not. They may not have transportation to a physician's office, community health center or hospital outpatient center. They may not have the money for even the modest co-payments that are often required these days. They may have rotated on and off the program so often that they don't even know if they have coverage. They may be so used to gaining access to care through the hospital ED that they don't know any other way of doing so. There are language issues, class issues, cultural issues.

And, frankly, many physicians aren't eager to treat this population. As a physician once told a Medicaid director, "The status of a physician is tied to the status of his patients." Treating lots of Medicaid patients won't gain anyone points at the country club. It is to their endless credit that so many physicians continue to do so anyway.

But the percentage is dropping. According to the National Center for Health Statistics, as of 2013, although 95 percent of physicians were accepting new patients, only 68.9 percent were accepting patients with Medicaid coverage.

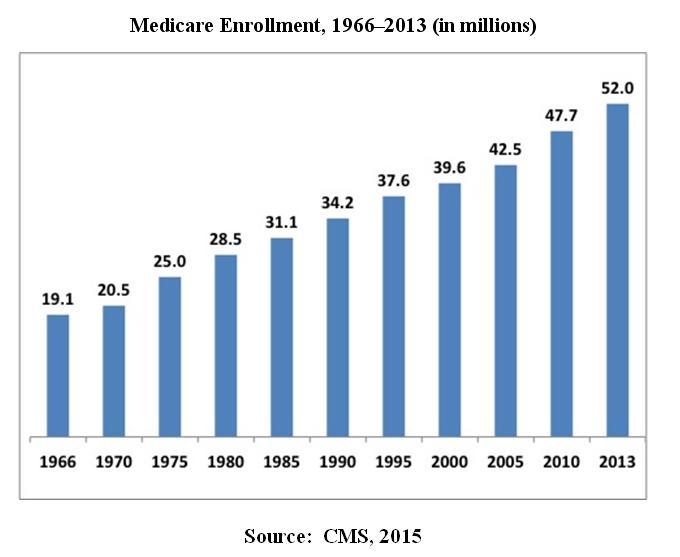

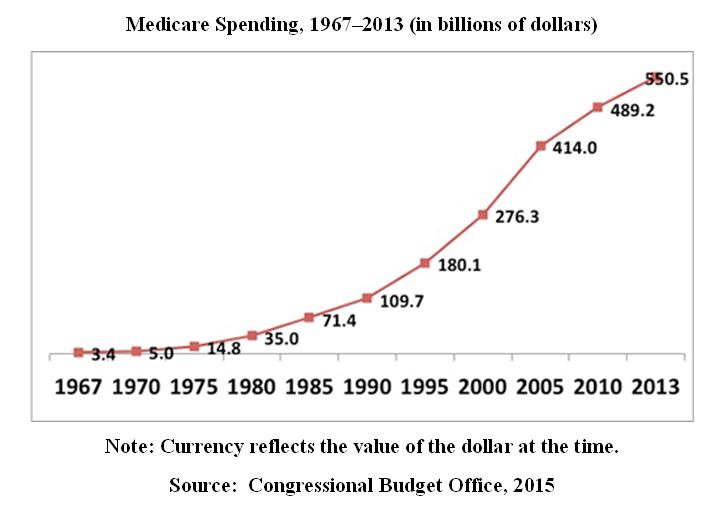

Medicare has been on a journey of its own. It, too, has changed repeatedly, as enrollment has just kept growing.

|

Perhaps the most interesting event was in 1988, when the Medicare Catastrophic Coverage Act was passed. The act included prescription drug coverage, expansion of long-term care benefits and Medicaid coverage of low-income Medicare beneficiaries. However, beneficiaries would have to pay for some of the costs, and that produced a firestorm that culminated with a group of angry seniors cornering then-Rep. Dan Rostenkowski (D-Ill.), the powerful chair of the House Ways and Means Committee, in his home district. One woman, Leona Kozlen, threw herself onto his car as he sought to leave. So much for that idea.

Most provisions of the law were repealed in 1989 (Medicaid coverage of extremely low-income, frail Medicare beneficiaries was retained). That failure taught a profound lesson to political leaders: If you are going to mess with Medicare, be careful. Its constituency has a lot more clout than its less fortunate Medicaid cousins.

In 2003, however, the Bush administration managed to get Medicare Part D passed, so prescription drug coverage was finally available to beneficiaries. However, it is a tricky law, and its most unattractive trick is that the traditional Medicare program is prohibited from bargaining for discounts on prescription drugs. This was part of a larger strategy to privatize the Medicare program, which began with the passage of Medicare Part C in 1997, which allowed beneficiaries to join private health plans. Medicare Advantage (MA) plans can negotiate for lower prices on pharmaceutical products.

Although Medicare has not been privatized, MA has made major gains; 15.7 million people out of the 52 million Medicare beneficiaries now belong to these plans, and estimates are that as many as 40 percent of baby boomers newly entering the program are opting for MA coverage.

At the same time, there are major ongoing fights. One is the "narrow networks" issue, which is not confined to Medicare, but does affect it, as beneficiaries discover that a favorite provider is excluded from the network. Sometimes they are presented with massive bills from an out-of-network provider.

Also, an obscure federal law that sought to limit increases in Medicare payment to physicians led to the long-term battle over the sustainable growth rate (SGR), which threatened to cut physician payments by as much as one-third. Always comfortable with kicking the can down the road, Congress for years postponed implementation of the limitation, as physicians wrestled with trying to plan for an uncertain future. Finally, in April of this year, Congress passed and President Barack Obama signed the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015, which repealed the SGR and supposedly set in motion a new payment scheme involving value-based reimbursement, pay for performance and quality reporting (before we get all excited, let's see what the regulations look like).

And there are still those who want Medicare privatized, which could happen over time anyway, given the growth in MA enrollment. But it is important to remember that MA plans are still paid largely with taxpayer money. And, in an aging society in which the youngest boomer turned 50 last year, Medicare spending only will increase. It is estimated that by 2024, it will total $858 billion. Public money will always largely fund this program.

|

We may hate Medicaid and Medicare; we may love one or the other. But, we should keep in mind that these programs cover 122 million Americans — 44 percent of the population — and soon enough, the majority of the population will have public coverage. Health Management Associates, a consulting firm that specializes in public programs, estimates that by 2025, 51 percent of Americans will have public coverage through Medicare, Medicaid, CHIP and insurance obtained through public exchanges (I'm not sure, however, that the latter group really constitutes people with public coverage; many of them are just subsidized).

Given Medicaid managed care and Medicare Advantage, some of that coverage technically will be private insurance, but it will be paid for, at least in part, with public money. And attempts at total privatization likely will meet stiff opposition, not only from those who do not believe in private insurance, but also from those who have benefited from these programs over the years, who are doing so now and who will do so in the future.

Have these programs made a difference in the health of Americans? As the statisticians say, it is difficult to prove a negative — that is, how many people would have died unnecessarily or suffered avoidable disability because Medicare and Medicaid did not exist.

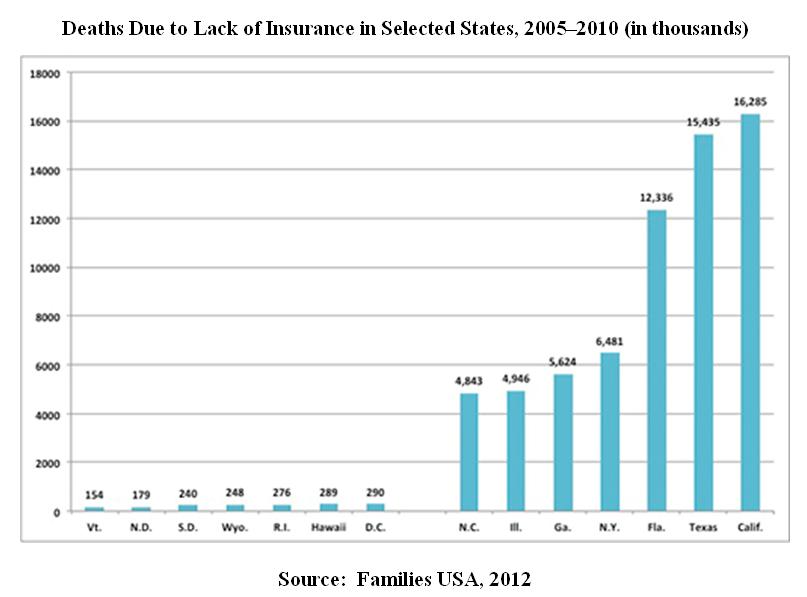

There are no reliable statistics of which I am aware. But Families USA published this chart in 2012 that showed how many people, in the organization's estimation, died between 2005 and 2010 because they did not have coverage. (Be aware that the larger numbers are, for the most part, from more populous states.)

|

Another, albeit small, study by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities found that among African-Americans, having Medicaid coverage reduced hospitalization by as much as 8 to 13 percent, and ED visits by as much as 3 to 4 percent. The latter number is no surprise; people without coverage learn early that the ED is their lifeline.

Medicare and Medicaid have made a difference in at least three other ways. One, which may seem to be a frill except to those who have been uninsured, is a sense of dignity, of having coverage, of not being forced to beg for care. The great singer Billie Holiday used to say that no matter what anybody offers you as charity, "God bless the child that's got his own." It was the title of one of her most unforgettable songs.

And although Medicare has been credited with desegregating American hospitals, that was largely accomplished by the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (see my article from last year, "U.S. Hospitals and the Civil Rights Act of 1964," published in Hospitals & Health Networks Daily on June 3, 2014). However, Medicare did force holdout hospitals to desegregate by threatening to withhold program payments.

And although data are sketchy and in many cases unreliable, Medicaid and Medicare likely have contributed to a lessening of the racial and ethnic disparities that plague many minority groups in the United States, from lowered life expectancy to later diagnosis of cancer to inappropriate treatment for diabetes. These disparities have proven to be far more difficult to address than anyone thought, but some progress has been made. Coverage is not the complete answer, by a long shot, but it has helped.

Finally, we tend to speak of Medicaid and Medicare in terms of financing, program design, policymaking and the endless wonky details. We have been fighting over these programs for 50 years — over who is covered, how they are covered, who pays what and whether they should exist at all.

But somehow, through all the fog and mist and bad data and ideology and politics, Medicare and Medicaid are still with us, 50 years after their birth, providing coverage to 122 million Americans. And they represent more than just a couple of insurance programs. They represent one of the few times in this country's recent history when we were willing to try to protect the less fortunate, when we attempted — in efforts however flawed — to do the right thing. That has become rare in our society, which recently was named, in terms of income, the most inequitable on Earth. Medicare and Medicaid represent something more fair and just.

As the great Princeton economist Uwe Reinhardt once wrote, the 1960s were the time when the people of the United States forced their country to live up to its own Constitution. Medicare and Medicaid remain as evidence of that commitment.

Kenneth Williamson, at the time the associate director of the AHA and one of the architects of Medicare and Medicaid (who has never received the credit he deserved for his efforts), wrote of P.L. 89-97, "Although some of the implications of this new law can be visualized at this time, there is much that cannot. Only time and experience will reveal its full impact. One thing is certain: It is a new day in health affairs. Things are not the same, either, for hospitals or physicians or the public. Things will never be the same again."

Truer words were never written. The changes the law wrought produced a hash of good, bad, different and irrelevant. But most important was the fact that for once in its selfish life, the United States chose to take care of its own people.

Happy birthday, Medicare and Medicaid.

Copyright © 2015 by Emily Friedman.

Emily Friedman is an independent writer, speaker and health policy and ethics analyst based in Chicago. Her website is EmilyFriedman.com.

Return to Emily Friedman home page