Return to Emily Friedman home page

By Emily Friedman. Originally published in Hospitals & Health Networks OnLine, December 6, 2011

From aging to generational change, the 2010 Census has major implications for health care providers.

The 2010 Census found that ethnic, racial and religious diversity in the United States increased markedly between 2000 and 2010. Cultural competence, workforce changes, and shifts in community health needs all will be on the agenda. This is the second of a two-part series — Part 1 was published on Oct. 4, 2011.

There are significant Somali populations in Lewiston, Maine, and Columbus, Ohio. The second-largest Cambodian population in the United States is in Lowell, Mass. The largest Arab-American community is in Dearborn, Mich. Vietnamese folks have been living in south Texas for decades. One in five Chicagoans is Latino. Nearly 40 percent of the population of New York City was born in another country. In California, 42 percent of the population is nonwhite; in Alaska, more than 3 percent of the population is African-American. North Carolina's population is nearly 9 percent Latino, and more than 7 percent of Washington State's population is Asian-American.

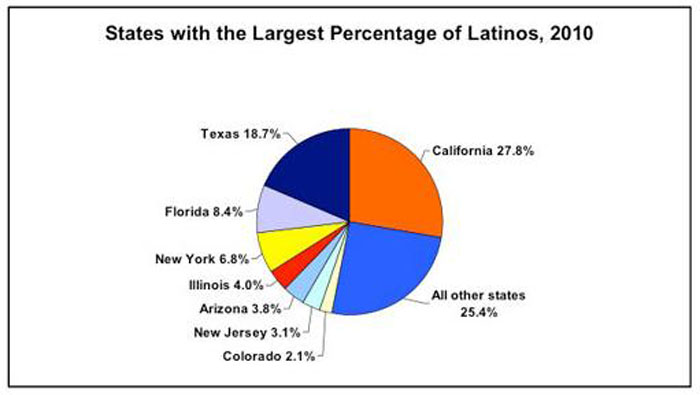

It's time to get over the stereotypes. Population diversity is not only alive and well in this country, but it is also getting more complicated. (For the overall breakout of the findings of the 2010 decennial census, please see the first part of this series at H&HN Daily or on my website, www.emilyfriedman.com.) To recap, about two-thirds of our population are non-Latino whites, and the largest minority group is Latino, followed by African-Americans.

But, as the statistics at the beginning of this article indicate, Americans — especially minorities — do not necessarily live where we think they do. For decades, most of us have had this stereotypic belief that Latinos live in the Southwest (which is still largely true for most of that group, but not for all of them by a long shot), African-Americans live in the South (also still largely true, although the two biggest urban populations are in New York City and Chicago, and more live in Cook County, Ill., than in any other county), and Asian-Americans live in San Francisco (that's a more complex issue, because the Census Bureau's Asian-American category encompasses a large number of groups, from people of Chinese heritage to people of Bangladeshi and Indian descent).

The fact is that people in this country have the luxury of internal migration — something we should not take for granted, as there are many nations whose citizens cannot travel freely — and they don't stay put. I mentioned in Part 1 of this series that we now have four "minority-majority" states, where whites are now a minority group: California, Hawaii, New Mexico and Texas. (Hawaii always had a minority majority.) According to the Population Reference Bureau, eight other states likely will qualify for this distinction in the next few years. In six of them — Arizona, Florida, Georgia, Maryland, Mississippi and Nevada — the population younger than 18 years is already minority-majority. The other two states are New Jersey and New York.

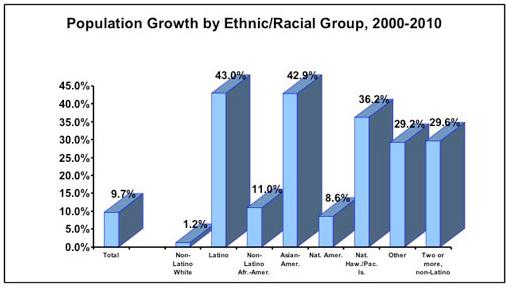

Many of these changes have to do with birth rates. Although there is a general belief that the growth in the Latino population is fueled by immigration (legal or otherwise), most of it is simply a case of a higher birth rate. From 2000 to 2010, the Latino population grew by 50 percent or more in 37 states, according to the PRB, and in nine states — Alabama, Arkansas, Kentucky, Maryland, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, South Dakota and Tennessee — it more than doubled.

Source: Census Bureau, 2011

The PRB further reports that the Asian-American population grew by more than 100 percent in Nevada in that same time period, and increased by 50 percent to 99 percent in 26 other states. This category had a growth rate equal to that of Latinos.

Source: Census Bureau, 2011

And it gets even more complex. Nine million people reported to the 2010 census that they had two or more ethnic heritages, representing about 3 percent of the country's population.

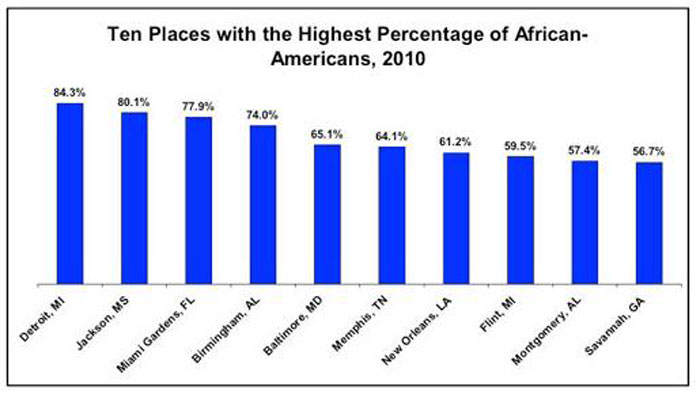

Still, many minority groups are concentrated in specific areas. The urban African-American population, by and large, is still located in the South, although not exclusively.

Source: Census Bureau, 2011

The rural African-American population also is still concentrated in Southern states.

In the wake of the election of President Obama, some commentators celebrated what they called the emergence of a "post-racial America." I would be delighted if we could ever get to the point when race and ethnicity don't matter, but we aren't there yet. And we may never get there. Racism, religious prejudice, segregation in its more subtle forms, lack of understanding and a lack of desire to understand are all part of our landscape, and will continue to be. Human beings are tribal by instinct, and our natural inclination, as Stephen Sondheim wrote in the score of West Side Story, is to stick to your own kind — however you define who that is.

Health care does not, however, have that luxury. So here are some suggestions for health care professionals and organizations regarding our ever-more-diverse patient and community populations.

Racial and ethnic disparities are not disappearing. Although a great deal of research (some of it highly repetitive, I might add cynically) has been done and many health care organizations are working mightily on the problem, minorities still face greater health care challenges, from an appallingly higher rate of African-American maternal mortality to lack of health insurance for Latinos.

The Census Bureau conducts the census every 10 years, but it also conducts an annual study, the American Community Survey, which asks different questions of participants and provides more detailed data. The 2010 ACS found that 15 million American children live in poverty. Nearly 40 percent are African-American and 32 percent are Latino; although it's no reason for pride, only 17 percent of white kids are that poor.

We can do better than this.

Specific population groups have specific disease predispositions. African-Americans are more likely to develop diabetes than whites. Latinos are far more likely to develop lupus. People of Jewish descent — particularly Ashkenazi — are prone to long clotting times because they are missing a certain blood factor. Asian-American women are at much higher risk of osteoporosis. In developing community screening, prevention and treatment programs, providers must know which populations are at high risk of what, and plan accordingly.

Community needs assessments must recognize who's in the community. Most responsible nonprofit hospitals and health systems already conduct community needs assessments, but now they are required by the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (the health reform law). Providers also must come up with a plan to address the needs that are identified. Although we don't know what will happen to PPACA in terms of the Supreme Court, these assessments are woven into the fabric of most nonprofit hospital and system planning. Identification of minority groups in the community, and their specific health care needs, must be part of the equation. If there is any lesson from our growing diversity, it is that one size no longer fits all, and never will again.

However, watch your data. As I mentioned in the first part of this series, the data are not always reliable — not because the U.S. Census Bureau is doing anything wrong, but because situations can change quickly. I learned recently that Latinos, who had a major role in fueling North Carolina's population growth between 2000 and 2010, are moving out of the state because of the bad economy. One report stated that two large buses a day were taking folks back to Mexico and coming back empty. Nevada was the growth child for population before 2008, but people are now fleeing the state because the housing bubble really burst there. New Orleans, which lost half its population after Hurricane Katrina, at times was the fastest-growing city in the United States as people came back. The decennial census is a 10-year snapshot that tells us where we've been and where we are now, but the situation on the ground can change very rapidly.

The ACS data may be more helpful to providers in their planning.

Cultural competence is not optional. The feds insist on it, the Joint Commission insists on it and most communities insist on it. Providers must be able to provide language interpretation and culturally sensitive care (for example, there are many cultures in which female patients will not be seen by a male physician), and would be well-advised to be competent in complementary and alternative therapeutic approaches as well. I have spent enough time in Cambodia to know that it is very common, especially among immigrant groups, to mix and match between Western and traditional medicine, and if you don't know what someone might be using on the side, the drugs you prescribe could be ineffective, or even worse, cause a harmful interaction.

Part and parcel of cultural competence is being able to communicate effectively. Professional interpreters are obviously the preferable alternative, but they may not always be available. And having staff members who can speak the patient's language is not sufficient; it is also necessary to train those staff members in basic clinical knowledge, explanation of complex health care issues to patients, and privacy of personal medical information. Most hospitals and health systems have rosters of employees who can speak different languages, but that's not enough. I have vivid memories of trying to interview a Cambodian hospital administrator and medical director when my interpreters were my friends who worked in a hotel. They couldn't translate many of my questions because they didn't understand them.

The American health care system developed as pretty much of a white-bread, English-speaking, middle-class operation, and we need to change.

Also, if there is any way that you can offer classes in English as a second language, do so; it might be the greatest gift you can give to your community.

Respect religion. I once worked for a health care organization that set the date for a board retreat on the holiest day of the Jewish calendar. In one hospital where I was employed, I always volunteered to work on Christmas and New Year's so my colleagues could be home with their families. Lunar New Year is the big deal for most Southeast Asians, and it occurs in April. During Ramadan, Muslims cannot eat during the day. Baha'i also requires a period of fasting.

Both as employers and providers, we need to respect people's religious beliefs and try to arrange that neither patients nor employees are asked or required to violate those beliefs.

The health care workforce is changing. I wrote earlier that health care does not have the luxury of ignoring the changing population, and that goes double for the workforce. There are three things going on: First, the older population of the United States is largely white, and the younger population is much less so, which means that those caring for older patients are likely to be of a different race or ethnicity, and that is likely to cause some tensions, at least at first.

Second, the same sensitivity to religion and cultural practices that patients need is also desired by employees. Know when the important religious holidays are. Know what the taboos are. I have always believed that nurtured employees provide nurturing care and, in this changing society, that has never been more important or necessary.

Third, intolerance on the part of employees is unacceptable. I remember the surgeon at a large health care system who announced that she would not operate on patients with HIV. The system sent out an all-employee memo that simply said, "If you won't treat patients with HIV, you don't work here anymore."

There are many privileges in health care work; picking and choosing isn't one of them.

In September, researchers at Johns Hopkins published a study in the Journal of the American Medical Association that was not surprising, but nonetheless disturbing. They found that a majority of medical students, in terms of who they wanted as patients, showed "an implicit preference for white persons and possibly for those in the upper class." Well, what a surprise! Most of the students were probably white and upper class.

But there just aren't going to be enough white, upper-class patients to go around, so maybe our medical schools should rethink what they're teaching our future physicians.

Speaking of which, who's on your board? The organization's board is its link to the community, the bridge, representing the core relationship to the people the provider serves. I know I've written about this before, but the message is important enough that I'll just repeat myself: An all-white, all-male board (with maybe one token female) in a diverse community isn't going to powder the doughnut. If you believe, as I do, that any health care organization is basically a community trust, then its board and executive leadership should look something like the community. And I have no patience with the tired excuse that there are no qualified female or minority candidates. Try looking for some; they might just pop out of the woodwork.

Address distrust. One issue that is hardly ever discussed is that there is widespread distrust of the health care system on the part of members of minority groups. I could tell you stories, from African-Americans who believe that hospitals kill them in order to get organs for white people's transplants, to Latinos who think that hospitals skimp on their care. Unfortunately, there are studies that back up some of these fears, although not the organ-donation paranoia.

It is almost impossible for a hospital or health system to serve its community if there is a segment of that community that doesn't trust the provider. Some of the fear comes from myth and old memories, some of it is misunderstanding and some of it may be rooted in truth.

Providers must reach out and try to address the fear, the distrust, the myths and the real negative experiences, and make it very clear that they get the message and want to be the healer of choice, the caregiver that understands. To go back to where I started, if we are really going to do something about racial and ethnic disparities in health status, this is where we need to begin.

Get used to it. Diversity is not going away. Maybe your institution or organization is located in a white suburb, but many members of minority groups are ambitious and entrepreneurial, and even if they don't make it to financial success themselves, most of them work very hard to see that their children will. And one day, you may wake up and find 10,000 Somalis in your service area, or an African-American neighborhood full of corporate executives, or a bunch of third-generation Latina moms with doctorates.

Get over it. This is your future patient population, your community and your future workforce. Learn. Adapt. Prepare. And enjoy every minute of it.

As my lifetime mentor and friend and former hospital administrator, the Rev. John G. Simmons, wrote in his just-published autobiography, "You have to be involved in the community if you want to be a community hospital."

Copyright © 2011 by Emily Friedman. All rights reserved.

Emily Friedman is an independent writer, speaker and health policy and ethics analyst based in Chicago. She is also a regular contributor to H&HN Daily and a member of the Center for Healthcare Governance's Speakers Express service.

The opinions expressed by authors do not necessarily reflect the policy of Health Forum Inc. or the American Hospital Association.

First published in Hospitals & Health Networks OnLine, October 4, 2011

GIVE US YOUR COMMENTS!

Hospitals & Health Networks welcomes your comment on this article. E-mail your comments to hhn@healthforum.com, fax them to H&HN Editor at (312) 422-4500, or mail them to Editor, Hospitals & Health Networks, Health Forum, One North Franklin, Chicago, IL 60606.