Return to Emily Friedman home page

First published in Hospitals & Health Networks OnLine, February 9, 2006

The changing fabric of American society affects everyone, but the health care system is particularly sensitive to demographic shifts. Health care leaders have the choice of seeing these changes as either obstacles or opportunities.

The majority of clients in a program for low-income expectant mothers in North Carolina do not speak English. A historically white-homogeneous town in Maine suddenly has a growing population of Somalis. Jamaican waitresses serve customers in a Missouri resort. More than a third of the population of New York City was born in a foreign country. Survivors of carnage in Sudan work in a Dallas hospital. In four states--California, Hawaii, New Mexico and Texas--the total of all minority residents exceeds the total of non-Latino white residents.

It should not be news to anyone that the United States has a diverse population; although our practice has not always been as pure as our posturing, we have traditionally prided ourselves on this aspect of our society. However, current and projected patterns of demographic change are more complex than they were historically, and the implications for the health care system are profound.

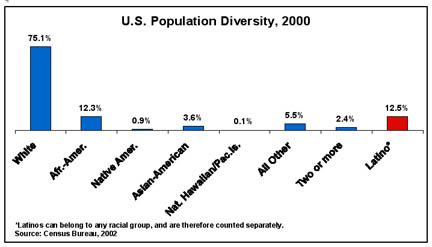

In the past few years, a number of population shifts have occurred. Today, more than 1 in 10 Americans was born in another country. Although that is not the highest percentage in history--that was 15 percent, in 1890--the main sources of immigration have changed; half of all U.S. immigrants are now from Latin America. Also, Latinos, at more than 40 million, have become the most numerous minority in the United States, outpacing African-Americans, who held that position heretofore.

Furthermore, the presence of minorities is being felt more in communities that historically have not been very diverse. Both native-born and immigrant minority Americans are moving to areas in New England and the Midwest, which traditionally were far less diverse than the South, the West and the industrial Northeast. One in every five Chicagoans, for example, is now Latino. And the diaspora of African-Americans displaced from the Gulf Coast in the wake of the hurricanes of 2005 is likely to lead to greater diversity in many communities.

Also, there are minorities within minorities. The Census Bureau--which in my opinion does a superb job of keeping track of our changing society--must use broad general ethnic and racial categories. So the "Asian" category includes people of Chinese, Japanese, Malaysian, Bangladeshi, subcontinental Indian and many other ethnic descents. "Latinos" can be of Mexican, Puerto Rican, Central or South American, or Cuban heritage. There are--or at least at one time there were--500 different Native American tribes. African-Americans can trace their roots to Africa, the Caribbean, Canada and elsewhere.

The tapestry of our population that is being woven today is thus far more complicated than what many people once saw as a black, white and red nation. Some of that color blindness was the product of ignorance, and some of it was simple bigotry; it was long conveniently overlooked, for example, that a major part of America's first great railroad system was built by Chinese immigrants. Pulitzer-Prize-winning cartoonist Thomas Nast in the 19th century portrayed Irish immigrants as apes. And until 1863, African-Americans in many states were considered to be property rather than human beings.

Diversity has always been fodder for political manipulation, unfair labor practices and social divisions. But it has also made the United States what it is, giving us everything from pizza and dim sum to jazz and blues, and gifting us with some of our greatest political, social and cultural leaders.

Growing diversity has an impact on all aspects of society, of course, but two sectors tend to feel it first: education and health care. The schools, hospitals and clinics in a community are likely to be the first organizations to know that a new group has come to town, or another group has experienced a population spurt, or a particular health condition is affecting one group more than another.

The health care system has usually tried to respond positively to these challenges--but not always. Although some hospitals were never racially segregated, the majority of them were in the 1950s when Robert M. Cunningham Jr., editor of what was then Modern Hospital, issued a courageous call for desegregation of health care institutions. He did this despite the fact that the 1946 Hill-Burton legislation had specifically included a provision for "separate but equal" hospital facilities for minorities. Then the Civil Rights Act was passed in 1964, and Medicare and Medicaid in 1965. In an equally courageous move, Surgeon General William H. Stewart, on March 4, 1966, wrote to every hospital in the United States demanding full compliance with the Civil Rights Act from any hospital seeking to participate in Medicare, which was to be launched on July 1 of that year. Several hundred hospitals protested, but eventually they complied with his demands and desegregated.

Even today, the situation is hardly perfect. Research by Professor James Fossett has found that in one major U.S. city, as the proportion of African-American residents rose in a neighborhood, the number of physicians willing to accept Medicaid patients declined. Professor Alan Sager has conducted research showing that both baseball stadiums and hospitals tend to close and relocate as minority populations rise in a city. And just last month, USA Today (Jan. 3, 2006) pointed out that much of the current hospital building boom is occurring in affluent white suburbs.

On the other hand, many health care providers and insurers have developed highly creative and effective programs for serving minority patients and communities. Henry Ford Health System in Detroit, recent winner of the McGaw Prize, has a program designed to improve the health of African-American men, often a forgotten target population. Bon Secours Health System in Baltimore has undertaken a broad community improvement program that includes education, job training and even assistance in management of finances and preparing for home ownership. Parkland Health and Hospital System in Dallas has welcomed refugees from Sudan as employees. Many hospitals offer instruction in English as a second language and assistance in obtaining a GED. Kaiser Permanente trains and certifies employees in multilingual and multicultural skills. There are many other outstanding efforts.

Creativity is certainly needed, because the challenges presented to health care by shifting population patterns are significant. Among the key areas:

Disparities in health status. Although it has become a hot topic recently, this issue is hardly new; civil rights leader W.E.B. DuBois wrote about disparities in the health status of African-American men, and issued a call to action, a century ago. But these days it is both a social and political issue; Senate Majority Leader Bill Frist (R-Tenn.) has said that one of his priorities is reducing health status disparities. Several federal agencies, notably the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (www.ahrq.gov), are involved in efforts to learn more about disparities and how to address them. State and municipal governments are also interested, as are private insurers.

This is an extremely complex issue, with many factors--social, biological, historical, genetic, lifestyle, psychological and cultural--involved. But research has also shown that disparities in health status are often linked to disparities in medical care, including lack of access, lower quality, poor communication with providers and real or perceived discrimination. An increasingly diverse patient population requires an elevated commitment on the part of providers to equal care for all.

Access to care. Professor Sager's decades-long work on hospital closings has shown us that in many minority areas, finding a physician, getting to a hospital or obtaining an appointment at a community clinic can involve very long waits, if it is possible at all. The USA Today story indicated that a sort of "hospital white flight" is taking place, as inner cities lose their health care institutions. Although suburbs full of luxurious and "niche" specialty hospitals competing for affluent patients' trade may fulfill some theoretical economists' vision of a "health care market economy," we might ask ourselves what kind of society tells American citizens that they can either take two buses and a train to receive care at a hospital 30 miles away, or they can just do without.

Insurance. Even if there is a hospital or clinic or medical practice around the corner, members of minority groups can have a hard time accessing it. These folks are much more likely to be uninsured (one third of Latinos lack any kind of coverage) or to have Medicaid coverage, and we all know what has happened and is going to happen to Medicaid and its beneficiaries in many states. Low provider payment rates, beneficiaries being tossed out of the program and limited coverage of services can lead to Medicaid being little better than no coverage at all.

Also, the rapid growth of high-deductible health plans, which often require a massive outlay of cash from policyholders, may be a good deal for the wealthy and healthy, but they are a disaster for low-income workers, who are far more likely to be minorities and are much less likely to be able to pay a $1,000 deductible.

The health care workforce. The workforce of the health care system--which by some counts represents 1 in every 12 workers in the United States--has always been disproportionately female and minority. Depending on the job description, the vast majority of health care employees in a given type of work may be members of minority groups. Areas such as security, dietary, housekeeping and plant maintenance services are likely to qualify. Minority immigrants are likely to be heavily represented as well.

There is nothing inherently bad about this; health care offers a wealth of entry-level jobs, and I have worked a few in my time. But a problem arises if there is no chance for advancement. Although the profession has made some strides, the ranks of nursing are overwhelmingly white; medicine is more diverse, but not by much. Many technical professions, from physical therapy to laboratory science, are not famous for their large minority contingents.

What's wrong with that? Nothing, if you don't mind overlooking the fact that health care desperately needs new, younger workers. We all know about the aging of nurses, but many other health professions are not far behind. And as Frank Zappa wrote in "Trouble Coming Every Day," on the Mothers of Invention Freak Out album (released 40 years ago), if all you have to look forward to for the rest of your life is being a janitor, you might start looking elsewhere. Health care must have career ladders for the young minority workers it is trying to recruit, or it will not attract or keep them for long. (For more on this subject, see the excellent AHA report, In Our Hands: How Hospital Leaders Can Build a Thriving Workforce, 2002.)

Leadership. Meeting all these challenges, of course, depends on an organization having leaders who want to meet them successfully. The good news is that there are health care leaders all over this country who are committed to having their organizations be part of the tapestry of diversity--indeed, to having them be key parts of the tapestry. The programs that I have mentioned here, and others profiled in my new AHA report (see below), are evidence of that.

The bad news is that both health administration and governance, especially in hospitals and health systems, are still dominated by white people, usually men. Now, before anyone gets mad, let me assure you that there is nothing wrong with white men; some of my best friends are white men (really, honest). More important, some of the most successful programs in reducing disparities and opening the health care ranks to minorities have been championed by white men. But, given that white men are a minority themselves in this country, their continued domination of health care leadership creates three difficult situations:

Fortunately, real efforts are under way to thwart that sad possibility. The CEOs of two major U.S. health systems are African-American men, and one, Kevin Lofton of Catholic Health Initiatives, is the chairman-elect of the AHA. The Greater New York Hospital Association and the Tennessee and Texas hospital associations are involved in major efforts to alert hospital boards to exceptional minority candidates for governance positions. The Institute for Diversity in Health Management has several programs for encouraging and mentoring members of minority groups interested in health administration. The American College of Healthcare Executives conducts surveys on how much progress is being made; it also offers tools for health care leaders to assess their own organizations and where they stand.

Despite the politics of racism, the anger, the sensitivities and the resistance to change that sometimes makes health care more than a wee bit stodgy, a new understanding seems to be growing--an understanding that these population changes are not just challenges, but also opportunities for health care to show what it can do, and how well it can do it. Given how many people are watching, I hope that our system does just that.

Emily Friedman's new report on population diversity and its impact on the health care system, White Coats and Many Colors, was published by the American Hospital Association in January 2006. It is available on the AHA Web site (www.aha.org) in electronic form under "What's New." It can also be found on the AHA Policy Forum site (www.ahapolicyforum.org) and the AHA Diversity/Disparities site (www.aha.org/aha/key_issues/disparity/index.html). Print copies are not available.

First published in Hospitals & Health Networks OnLine, February 9, 2006

© Emily Friedman 2006