Return to Emily Friedman home page

First published in Hospitals & Health Networks OnLine, 27 July 2005

Medicaid, at the time a little-known part of the law that also created Medicare, has become the largest single health insurance program in the United States. What can we learn from its history, and what is its future?

Poor Medicaid. It pays for some or much of the care of more than 50 million Americans. It is the largest third-party payer of nursing home costs. It has provided protection for millions of children who would otherwise be uninsured. It covers services that Medicare does not for extremely vulnerable disabled people. It is a lifeline for most public hospitals and community health centers. Yet, to use the tag line of the late comic Rodney Dangerfield, it just can't get no respect. And these days, its very future is in doubt, as it faces potential enormous funding cuts and major reconfiguration on both the state and federal level.

So, as its 40th birthday approaches on July 30, it seems fitting to offer a few observations about this much-maligned, yet vital, program.

Medicaid has spent much of the past 40 years flying under the health policy radar, although that has changed radically in the past few months. Even at its birth, few people paid any attention to it.

The colorful story of how it came into being has been told many times. (See, for example, Emily Friedman, "The little engine that could: Medicaid at the millennium," Frontiers of Health Services Management vol. 14, no. 4 (Summer 1998).) Suffice it to say that several forces converged to create it in the summer of 1965: the desire of powerful Congressman Wilbur Mills (D-Ark.) to continue federal support of health care for the poor, which had begun with the Kerr-Mills Act in 1960; the Johnson administration's efforts to placate state governments who were unhappy that Medicare was to be a federal program and wanted something of their own; concerns on the part of conservatives that Medicare was a "foot in the door" for national health insurance, which could be allayed if a program controlled by the states was part of the Medicare bargain, thus preventing a single, universal approach; and pressure from hospitals for relief in caring for the uninsured poor. Indeed, after some initial resistance, even the American Medical Association supported the proposal, although it maintained its vehement opposition to Medicare until the bitter end.

Unfortunately, Medicaid came into this world with severe birth defects. First, it was kept separate from Medicare, not only in the legislation, but also in its administration, funding and structure. Thus it has rarely been able to benefit by association with the much more popular and politically powerful Medicare program; it was, and still is, a stepchild. Karen Davis, president of the Commonwealth Fund, has called this separation one of the biggest mistakes in the history of American health policy because it left the more vulnerable populations alone in a more vulnerable program.

Second, Medicaid does not have the broad constituency of Medicare, which is essentially a universal entitlement for people over 65. Medicaid serves low-income children, families and some childless adults; people with HIV and AIDS; people with disabilities; nursing home patients; and low-income elderly people who cannot afford Medicare co-payments and deductibles. It also subsidizes hospitals that care for large numbers of publicly insured patients. And it does a few other odd jobs. As a result, no one constituency represents the whole program; it is splintered, which is never a good idea when fights break out.

Third, as health care consultant William Copeland noted recently, "The program is large, complex and incoherent." In a history of Medicaid that I wrote when it was only 10 years old, I observed that no one knew what was going on with it--and it was much simpler then than it is today. Although the decision to make it state-administered was politically necessary, it has left a messy legacy.

There are 53 separate Medicaid programs. Coverage of some constituencies is federally mandated, but states can choose to cover other "optional" groups, using state money. Financing is shared by the federal government and states, and everyone knows how much fun that can be. Each state can cover different services for the "optional" groups. Federal waivers are available to experiment with different ways of structuring the program. Income standards for eligibility vary by state. All but three states now enroll some or most beneficiaries in managed care. And on and on.

This makes Medicaid a policy wonk's fantasy, and many analysts confess that it is their favorite program to study. But its almost incomprehensible complexity makes it hard to understand, harder to explain--and even harder to defend when it is attacked.

Medicaid's fourth problem is that from its inception, it has been both unpopular and vulnerable politically. The basic reason is not complicated (one of the few aspects of this program that isn't): It costs a lot. A whole lot--well more than $300 billion annually. No one, including the people who wrote the original legislation, believed that there were very many people who would need this coverage; one estimate was maybe 3 million. At the moment, nearly one in five Americans is eligible for it.

Although it has been suggested that there was manipulation of data by those who wanted to see the legislation pass, history strongly suggests that there weren't very many numbers to manipulate. After all, the first modern national study of insurance in the United States would not be conducted for another 11 years. The legislation's framers were guessing, and they guessed wrong.

Medicaid's political fortunes, however, were the product of more than cost; there was also the issue of who was receiving the benefits. For much of its existence, Medicaid was tied to the welfare system, which I think was almost as bad a mistake as keeping it separate from Medicare. And although most beneficiaries are white, minorities are disproportionately represented among its constituents.

Furthermore, although it is profoundly inaccurate, the image has been created by those not enamored of the program that its benefits largely go to legions of lazy, non-white, drug-addicted welfare bums. Given that its tie to welfare was severed years ago and that most of its beneficiaries do not receive welfare payments, that most addicts are specifically barred from eligibility, and that more than half of all Medicaid beneficiaries are members of families with at least one working member, this perception is wrong both factually and morally.

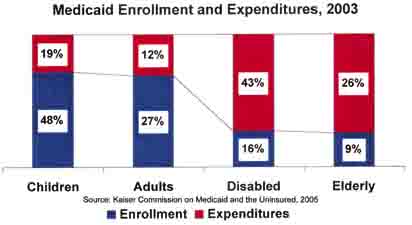

The truth is that although the majority of beneficiaries are low-income children and adults, the majority of spending is on the elderly and disabled.

This has, at times, produced an exceptionally ugly fight over whether those greedy old geezers are stealing bread out of the mouths of babes. Anyone who stops to think about it for, say, five seconds, would realize that care for healthy kids costs a lot less than care for demented, diabetic 85-year-olds. Nonetheless, last month Congressman Joe L. Barton (R-Texas) predicted that "the emotional debate that we're eventually going to have to have is the old-versus-the-young debate. Two-thirds of the dollars in Medicaid go to old people when two-thirds of the needs in terms of health care are in children and young people." There's nothing like setting two vulnerable groups to fighting each other over scraps.

So Medicaid's political fortunes have been problematic; indeed, it has been drop-kicked so often that it could qualify for use by the National Football League. At the beginning, once expenditure figures started coming in, Congress began enacting cost containment measures before all the programs were even up and running. Over the years, Medicaid beneficiaries have been subject to lowered income standards for eligibility; reductions in services; skimpy payments to providers that have led many of them, especially physicians, to refuse to participate in the program; complex enrollment and renewal procedures that, intentionally or not, are discouraging if not intimidating; limits on access to pharmaceuticals; and enormous growth in either voluntary or mandatory managed care, in which 60 percent of all beneficiaries are now enrolled.

There have also been more innovative efforts. The much-vaunted experiment in Oregon reduced the number of services available, with the savings targeted to covering more people. Unfortunately, the program has fallen victim to high costs and is rapidly on the way to being in tatters. Tennessee inaugurated TennCare, claiming the state was on the road to universal coverage, placing beneficiaries in managed care and greatly expanding enrollment; this experiment, too, has hit the wall, and a battle (apparently a losing one) is under way to prevent 323,000 people from being dropped from the program.

Several states, including Connecticut, Maryland and Illinois, have proposed or approved legislation requiring large employers to cover their workers or at least spend more on employee health insurance. Aimed largely at Wal-Mart, these bills would not survive a court fight because such employer mandates are illegal under federal law; however, they have brought attention to the fact that many employees of Wal-Mart and some other large discounters are on Medicaid. The Maryland law was passed, but was vetoed by the governor; we can expect more activity on this front, purely symbolic though it might be.

Arizona's managed care experiment, which pioneered the concept, has by most accounts been quite successful for those who qualify, but eligibility standards are tight, and a recently passed referendum prohibiting the use of state services by undocumented immigrants is likely to cause problems in that border state. Colorado, Maryland and Massachusetts are embroiled in debates over their efforts to reduce or eliminate benefits for legal immigrants. California just cut a deal that will increase federal funds while reducing the number of participating hospitals and forcing more than 500,000 elderly, blind and disabled residents into managed care.

Other plans are in the works. Florida wants to turn the program over to private health plans; South Carolina is also considering privatization. These and other proposals that have surfaced require federal approval, but it is likely to be forthcoming, given that the current Secretary of Health and Human Services, Mike Leavitt, is the former governor of Utah, where he inaugurated a program, with federal approval, under which many Medicaid beneficiaries are eligible only for primary care.

But some states are still doing things the old-fashioned way. Missouri is in the process of terminating eligibility for 100,000 beneficiaries, and other states are considering similar cuts.

What has now erupted is a battle royal over federal funding for the program. During his confirmation hearings, Leavitt told the Senate that he knew of no plans to replace Medicaid or turn it into a block-grant program, but he was vague about the possibilities of other cost containment efforts. No one should have been surprised, then, when earlier this year, the Bush administration and many of its congressional allies proposed sweeping cuts in federal spending on the program, to the tune of $15 billion.

Governors and consumer groups reacted with alarm. The National Governors Association (NGA) began working on a plan of its own. A massive arm-wrestling match erupted as the House passed a budget template that included $10 billion in Medicaid cuts over five years. It looked like the Senate might follow suit, but the proposal failed by one vote. A compromise was eventually struck, or so people thought, when Leavitt agreed to appoint a bipartisan commission that would find ways to cut $10 billion without harming beneficiaries. The Senate agreed. Then Leavitt announced that he and he alone would appoint all the voting members; the congressional appointees would be nonvoting observers.

That went over well. Congressional Democrats announced that they would boycott the commission. The NGA followed suit. As of this writing, there is some question as to whether congressional Republicans will participate, as several powerful members are expressing reluctance. Meanwhile, the NGA has produced a Medicaid "reform" plan of its own, which calls for more flexibility for states in configuring the program, but, of course, no reduction in federal funding.

Other challenges to the cost-cutting juggernaut have emerged, producing some fascinating bedfellows. The American Association of Retired Persons, whose support was crucial to passage of the Medicare Modernization Act, has entered the fray, strongly opposing cuts--possibly because some in Congress are now talking about limiting seniors' ability to hide or transfer assets in order to qualify for nursing home coverage under the program. Pharmaceutical manufacturers, who have a lot to lose, have also gone on record opposing the cuts. Given the huge proportion of Medicaid spending that goes to pharmaceuticals, their position is understandable; in Tennessee, for example, drugs represent 50 percent of all program spending. Speaking of Tennessee, its governor, Democrat Phil Bredesen, seeking to implement the largest enrollment reduction in Medicaid history, spent more time in court lately than Michael Jackson as consumer advocates fought to stop the cuts. Although he won, Bredesen has been bruised politically.

No one knows how all this will play out, but it seems probable that significant cuts will be made in Medicaid on both the state and federal level before Congress adjourns for the year. The trade-off will likely be more flexibility for the states, which could lead to innovative improvements, but could also lead to wholesale loss of all or most coverage for millions of people. Frankly, depending on the state, both developments can be expected.

What can be learned from this tangled history? First, any state budget is a political critter, of course, and if a program represents the largest percentage of spending, as Medicaid does in almost all states, it has to be examined. A burgeoning federal budget and enormous deficits are just as politicized, and it is hardly a secret that opinions differ profoundly on what priorities should be. Medicaid is a public program; it is subject to the whims of government. That doesn't mean that every time government needs a whipping boy, it should immediately start kicking Medicaid around.

Second, Medicaid has taught us, more than any other program, that if you make things really complicated, you will have problems down the line. Whether I agree with their decisions or not, I have great sympathy for state and federal legislators and staffers as they try to figure out how to get a handle on this thing. And even if you do attain a momentary understanding, it won't last; Medicaid is like those morph-y things in the awful Terminator films that keep changing into something else right before your eyes. It defies understanding. That is unlikely to make for either good policy or optimum practice.

Third, years ago, the late Wilbur Cohen, who was an HEW official in the Johnson administration and is considered by many to be the father of Medicare and Medicaid, told me that "a program for the poor is a poor program." By no means does it have to be; but given the judgmental nature of this society, it is likely to be. As health care analyst and philosopher Roger Evans has written, to be poor in America is to fail, and "this country does not like to reward failure." Ironically, Medicaid may survive, not because of the invaluable protection it has afforded to poor children and families, but because of its benefits for more politically influential seniors, who were never supposed to be a significant part of the program's equation.

Fourth, the passage of Medicaid and its continued existence offer proof that ours is not a heartless society. At the recent annual meeting of AcademyHealth, James Mongan, M.D., president and CEO of Partners HealthCare in Massachusetts, who was a Senate staffer at the time Medicaid was created, asked a poignant question: "What ever happened to social justice?" He went on to say that historically in the United States, the healthy subsidized the sick and the wealthy subsidized the poor, and no one saw anything wrong with that. He suggested that we have in recent decades "taken a wrong turn" and moved in the direction of every-man-for-himself, which is a fatal situation for those who are poor, disabled, mentally ill, chronically sick, demented, very young, very old or otherwise compromised--the very people whom Medicaid protects.

With Medicare facing radical change next year and Social Security potentially subject to the same, Medicaid remains a symbol of the willingness of Americans to share with people who are not so fortunate as themselves. To lose it, or to compromise it beyond salvation, would be to lose a part of this nation's soul.

Diane Rowland, executive director of the Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, pointed out at the same conference that Medicaid provides coverage for 40 percent of people living in poverty, 21 percent of those in near poverty, 26 percent of all American children, 50 percent of poor children, 37 percent of pregnant women, 20 percent of people with severe disabilities, 44 percent of people with HIV and AIDS, and 60 percent of all nursing home residents. "Medicaid," she concluded, "has done a great deal of heavy lifting during its 40 years."

It's time we gave it some help.

Happy Birthday, Kid.

First published in Hospitals & Health Networks OnLine, 27 July 2005

© Emily Friedman 2005